February 18, 2025 marks the second anniversary of Late Prof. Mark Burgin’s passing away leaving a wealth of information in many books, papers in several journals and International Conferences for us to update our knowledge. I had the privilege of learning about the General Theory of Information and work closely with him to develop several applications of the theory to build a new class of distributed software applications with self-regulation and cognitive capabilities integrating current symbolic, and sub-symbolic computing structures with super-symbolic computing.

My collaboration with him started in 2015, when I discovered his book super-recursive algorithms discussing the limitations of traditional Turing machines. Burgin argues that Turing machines are limited to computable functions, meaning they can only solve problems that are algorithmically solvable within their framework. This exclud.es certain complex problems that require more advanced computational models. I shared with him my paper presented at the Turing Centenary Conference (2012) “The Turing O-Machine and the DIME Network Architecture: Injecting the Architectural Resiliency into Distributed Computing” which suggested a way to go beyond the limitations to design, develop, and deploy distributed software applications with higher resiliency, efficiency and scalability. He offered to meet with me to discuss how his recent work on General Theory of Information could extend the efforts to improve information systems.

Our collaboration resulted in several papers and implementation of a new class of autopoietic and cognitive distributed software applications.

Being and Becoming:

The phrase “from being to becoming” which, has its roots in ancient Greek philosophy, signifies a concept that contrasts two states of existence: being and becoming. Being refers to a state of existence that is static, unchanging, and eternal. It represents the idea of something that simply is, without undergoing any transformation. Becoming, on the other hand, is about change, growth, and transformation over time. It emphasizes the dynamic and fluid nature of reality, where things are constantly evolving and developing. According to Plato, the physical world we perceive through our senses is not true reality. Instead, the true reality consists of abstract, perfect, and unchanging entities called Forms or Ideas. These Forms are the perfect blueprints of all things that exist in the physical world. The concept of being and becoming underscores the importance of change, growth, and transformation in understanding human existence and the nature of reality. They suggest that rather than being static entities, we are constantly evolving and shaping our identities through our experiences and actions.

General Theory of Information:

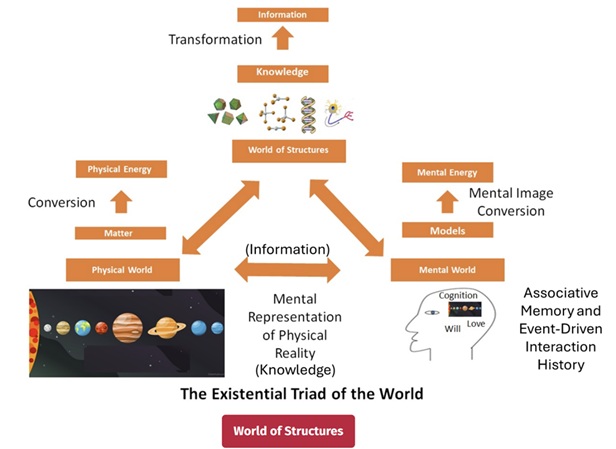

Mark Burgin provided a scientific interpretation of Plato’s Ideas/Forms with the General Theory of Information (GTI) by introducing the concept of the Fundamental Triad which relates the three structures:

- Material Structures: These are the physical entities and objects in the world. They represent the tangible aspect of reality that we can observe and measure.

- Mental Structures: These exist within biological systems, such as the cognitive processes in living beings. They represent the informational and cognitive aspect of reality.

- Ideal Structures: These are abstract, perfect entities or principles. They represent the highest level of information, akin to fundamental truths or laws of nature.

The three types of structures are interconnected and interact with each other. Material structures provide the physical basis for mental structures, while mental structures process and interpret information based on ideal structures. This triadic relationship helps in understanding the different aspects of reality and how they influence each other. Some examples of material structures are:

- Atoms and Molecules: The basic building blocks of matter.

- Biological Cells: The fundamental units of life.

- Machines and Devices: Physical tools and technology, such as computers and smartphones

Some examples of mental structures are:

- Schemas: Cognitive frameworks that help individuals organize and interpret information. For instance, a child’s schema for a dog evolves as they encounter different breeds.

- Memories: Stored information in the brain in the form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history that influences behavior and decision-making.

- Concepts and Beliefs: Mental representations of ideas and principles.

Some examples of ideal structures are:

- Mathematical Theorems: Abstract principles that describe fundamental truths in mathematics.

- Scientific Laws: Universal principles that govern natural phenomena, such as Newton’s laws of motion.

- Philosophical Concepts: Abstract ideas like justice, beauty, and truth

Figure 1 shows Mark Burgin’s representation of the interrelationships of the three structures.

In GTI, scientific laws are considered Ideal Structures because they represent abstract, universal principles that govern natural phenomena. These laws are perfect and unchanging, much like Plato’s Forms. They serve as guiding principles for understanding and interpreting the material and mental structures. For example, the laws of physics help us understand the behavior of physical objects (material structures) and can also influence cognitive processes (mental structures) through their applications in technology and science. Scientific laws facilitate the flow of information between different levels of reality. They provide a framework for predicting and explaining phenomena, thereby linking the material world with abstract concepts. These laws form the foundation for scientific knowledge and inquiry. They allow us to build models and theories that can be tested and refined, contributing to our overall understanding of the universe.

In the physical world, material structures are formed by matter and energy transformations obeying the laws of nature and these structures carry ontological information that represents their state and dynamics over time. Ontological information, in this context, refers to the intrinsic information that defines the existence and properties of material structures. This information is crucial for understanding how these structures evolve and interact within the material world. Their evolution can be described using ideal structures such as Hamilton’s equations (describing phase space evolution) or Schrodinger equation (describing the wave function evolution) depending on the structure and energy.

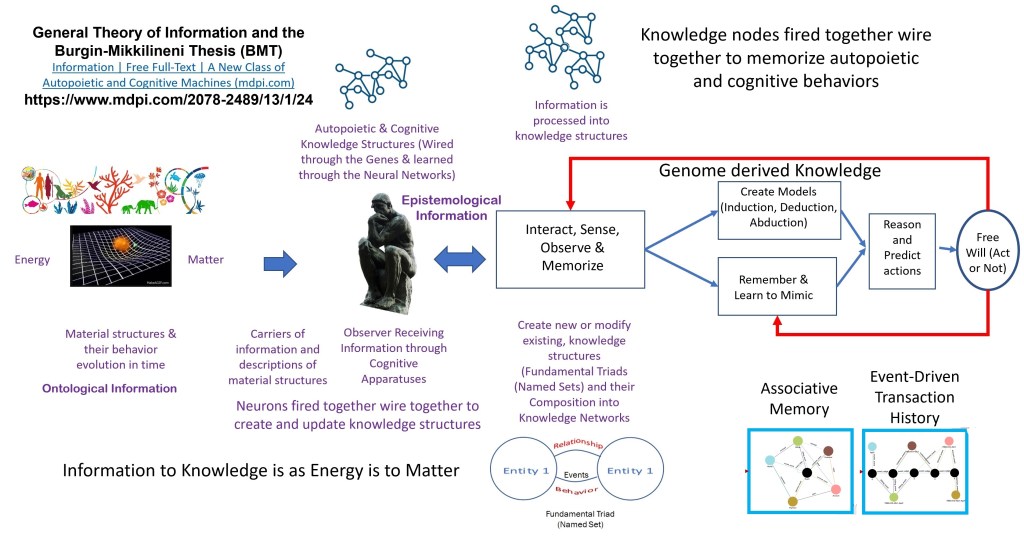

GTI bridges the gap between the material world (consisting of matter and energy) and the mental worlds of biological systems, which utilize information and knowledge to interact with their environment. GTI posits that biological systems are unique in their ability to receive information from the material world and transform it into knowledge in the form of mental structures. The knowledge belongs to the realm of biological systems and they maintain their structural identity, observe themselves and their interactions with the external world, and use knowledge to make sense of these observations. They inherit this ability through the genome passed on by the survivor to the successor in the form of encoded knowledge in the form of genes and chromosomes. They contain the operational knowledge to build, operate, and manage a society of cells that execute life processes. Each cell receives input and executes a process and shares output with other cells. A special type of cells called the neurons provide ability to receive information and convert it into knowledge stored in the form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history. When signals are received through their senses, the neurons fire together and wire together to process information and transform it into knowledge, Other neural networks use the knowledge to make sense of their observations and act based on their experience to optimize their future state.

Information, Knowledge, Intelligence, and Wisdom

At its core, GTI is built on the premise that information isn’t just data or knowledge, but a dynamic and process-driven concept that encompasses not just the static storage or transmission of data, but also the evolution and transformation of a system’s state through interaction and context. According to General Theory of Information, knowledge belongs to the realm of biological systems with the ability to process information received from material structures and represent the knowledge as a network of networks, where nodes and edges process information, store it, and communicate with others using shared knowledge.

Figure 2 depicts the relationships between material world and the mental world where knowledge exists.

Here are some of the key implications and consequences that GTI brings to software engineering, AI, and future technologies:

Designing Distributed Software Applications: GTI emphasizes the role of information flow and transformation in dynamic, distributed environments. In the context of distributed software, it suggests that systems must be designed to handle continuous change and context shifts in how information is interpreted, processed, and exchanged.

GTI’s focus on dynamic interactions and history means that distributed systems can evolve by leveraging historical interactions and context, leading to more adaptable, resilient, and self-organizing architectures.

Development of Super-Symbolic Computing: In the realm of AI, the notion of super-symbolic computing is particularly influential. Traditional symbolic computing uses discrete, formal representations (like logic and language) to represent knowledge. Super-symbolic computing, which extends this framework, considers more holistic, emergent forms of representing knowledge, especially as it relates to more complex, associative, and dynamic processes.

Adaptive Problem Solving: By incorporating GTI, systems can work with higher-level abstractions that are not strictly formal but are instead contextual and adaptive. This allows AI to handle more nuanced decision-making processes, potentially moving beyond rigid symbolic structures to more fluid and adaptive problem-solving methods.

Associative Memory: Associative memory in AI is a model of memory that doesn’t rely on fixed addresses or specific data retrieval pathways but instead stores information in a more contextually associative manner (like the way human memory works). This concept aligns with the GTI’s approach, which focuses on how information is not just static but is connected and evolves based on past interactions.

In distributed systems and AI, associative memory could enable more dynamic knowledge retrieval and adaptation, where systems can “remember” previous interactions, adapt to changing conditions, and even form new, emergent structures based on new inputs.

Event-Driven Interaction History: GTI posits that interactions (whether between humans, machines, or other systems) generate information that evolves over time. Event-driven systems, which are increasingly popular in distributed systems, can make use of this by tracking events as they occur, then responding to and evolving based on the accumulated history.

- In AI systems, this means that models could be better equipped to understand not just the current state but how that state has evolved, leading to a more nuanced understanding of context and history.GTI highlights the potential of composable, modular knowledge representation systems. By creating knowledge structures that can be pieced together and restructured dynamically, we can move away from rigid, one-size-fits-all models of knowledge.

- This is particularly important in environments like AI and distributed systems, where the complexity and diversity of information demand flexible, scalable approaches to how knowledge is represented and accessed.

Composable Knowledge Representation: In essence, the contributions of GTI, especially as extended by others, suggest a paradigm shift from traditional models of computation and information systems toward more adaptive, flexible, and context-aware architectures. This shift has the potential to reshape how we design and deploy technologies, especially in the realms of AI, distributed systems, and knowledge representation.

At its core, GTI is built on the premise that information isn’t just data or knowledge, but a dynamic and process-driven concept that encompasses not just the static storage or transmission of data, but also the evolution and transformation of information through interaction and context. Here are some of the key implications and consequences that GTI brings to software engineering, AI, and future technologies:

Designing Distributed Software Applications: GTI emphasizes the role of information flow and transformation in dynamic, distributed environments. In the context of distributed software, it suggests that systems must be designed to handle continuous change and context shifts in how information is interpreted, processed, and exchanged. GTI’s focus on dynamic interactions and history means that distributed systems can evolve by leveraging historical interactions and context, leading to more adaptable, resilient, and self-organizing architectures.

Development of Super-Symbolic Computing: In the realm of AI, the notion of super-symbolic computing is particularly influential. Traditional symbolic computing uses discrete, formal representations (like logic and language) to represent knowledge. Super-symbolic computing, which extends this framework, considers more holistic, emergent forms of representing knowledge, especially as it relates to more complex, associative, and dynamic processes.

Applications of the Theory

Hopefully, the General Theory of Information and Late Prof. Mark Burgin’s writings will inspire the next generation of computer scientists and IT professionals to critically examine our current understanding of both human and machine intelligence, especially in light of the General Theory of Information (GTI).

Human Intelligence: Flaws and Fixes

Human intelligence suffers from the self-referential circularity of the reasoning systems we use to process knowledge and interact with the world. Unless these systems are anchored to external reality with a higher-level reasoning framework, conflicting decisions from various logic systems lead to inconsistency. For example, the self-regulation mechanism of a system based on autocratic, oligarchic, and democratic axioms (statements or propositions regarded as self-evidently true) often results in conflicts due to their self-referential nature. These conflicts arise because the logics are not moored to external reality, as discussed in the book Life After Google. A higher-level reasoning system is required to address and resolve these inconsistencies. Clearly, current systems are not sufficient.

Machine Intelligence: Current State and Challenges

The current state of machine intelligence also has significant flaws. Sub-symbolic and symbolic computing alone are insufficient for reasoning based on both the current state and the history of the system. Large Language Models (LLMs), which are sub-symbolic computing structures, need higher-level modeling and reasoning systems to integrate the knowledge they derive. Autopoietic and cognitive knowledge networks must specify life processes and execute them using structural machines. Without a genome specification of life processes passed from survivors to successors, there is no true intelligence. Similarly, without a digital genome specification of machine life processes describing a particular domain (entities, relationships, and their behavior history), machine intelligence cannot be complete and consistent.

The Path Forward

Transparency and access to information at the right time and place, in real-time, can reduce the knowledge gap between various actors and potentially lead to consistent and value-added actions. Machines and their intelligence are designed by humans in the form of a digital genome that specifies the machine’s life processes. Facilitating transparency and access to information moored to external reality can augment human intelligence through machine intelligence.

Here is a video that chronicles my understanding of the evolution of machine intelligence influenced by my association with Mark.